On September 16th 2025, the world was alerted to a massive security attack on a number of NodeJS Packages. The full list of affected packages can be found here. The attack was worm-like, certain packages ran a malicious postinstall script on package load/install/update that scanned the repo for sensitive data and leaked it.

But how does anyone fall for this? You can track it down to two disappointing yet understandable reasons - default lifecycle script executions (more here) and automated package patching and updating.

lifecycle scripts in node 📜

With the introduction of the Node Package Manager (NPM) in 2010, its extensibility in allowing packages to execute scripts was very useful, especially when adding packages with non-JavaScript (JS) binaries. A lot of older packages and libraries rely on these postinstall scripts (scripts that run after the package is installed), and most of the time these scripts have unchecked access to the codebase and even the host machine!

So we can’t just disable this behavior, too many apps rely on it. And it’s also not the case that only legacy packages need this. Modern libraries like the prisma ORM also require postinstall scripts to execute 🤔

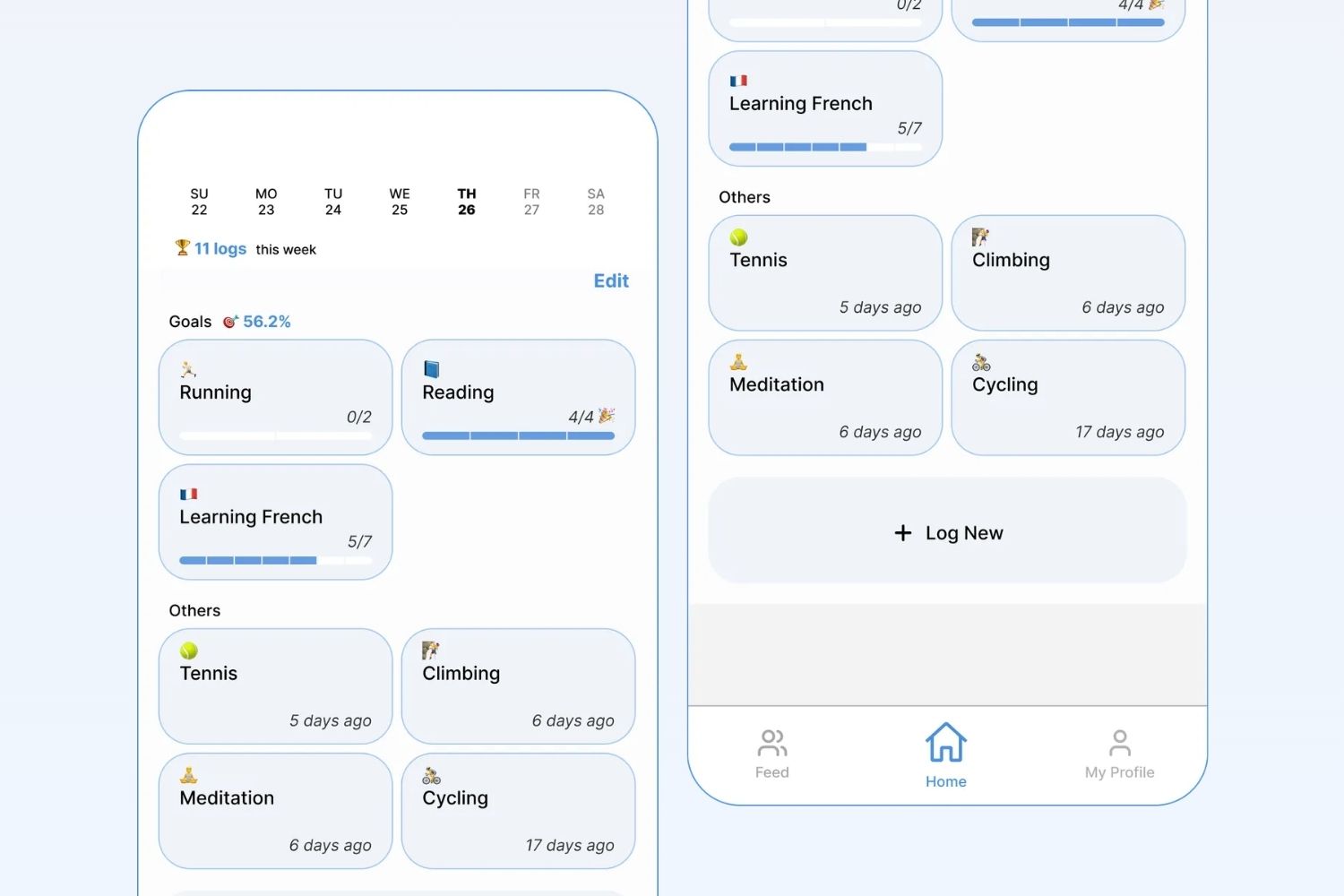

image source: https://www.varonis.com/blog/npm-hijacking

What seems like an obvious security flaw is actually the default behavior of package managers like npm and yarn (v1). Newer package managers like bun and pnpm disable these script executions by default. The best actionable here to most developers is to enable the ignore-scripts functionality in your package managers.

But there’s a bigger, silent behavior most developers have accepted as the status quo. One that is not only a security risk but can also be a source of hard-to-debug bugs: the fact that packages are automatically updated each time you add a new package or refresh your packages (each npm i or yarn install), and it’s up to the package creators to decide which ones should update!

some basic package manager context 🧐

A lot of JS/Node developers are either sub-consciously or consciously aware of this - when you clone a repository, or add a new package, all package managers need to run a module resolution process, an unsurprisingly complex process that is used to determine which versions of a package can be installed - and which other libraries your project has should upgrade/downgrade to accommodate it. A package manager generates this info each time on-the-fly, and it stores this info in something called a lock file

For example, let’s say we have a codebase with 1 package, package A, that depends on any version of another package, package B. Your lock file (in this example, I use yarn.lock) might look something like this:

"PackageA@1.0.0":

version "1.0.0"

resolved "https://registry.yarnpkg.com/PackageA"

integrity sha512-this-is-Package-A-sha512

dependencies:

"PackageB" "^1.1.0"

Let me break this down a little further:

- We installed a “PackageA” which has a semantic version of

1.0.0 - “PackageA” needs “PackageB” → “PackageB” is listed as a dependency

- “PackageA” needs “PackageB” but only if it is at least version

1.1.0 - And the version number prefixed by

^is not a typo,- The

^before1.1.0indicates that it can accept1.1.0or any minor version of PackageB that is v1.1.0 or greater (e.g.1.1.1,1.2.1, etc.) - FYI,

~is also sometimes used, so~1.1.0indicates that it can accept1.1.0or any patch version of PackageB that is v1.1.0 or greater (e.g.1.1.0,1.1.9, etc.)

- The

_With Semantic Versioning, we use 3 digits to date software, each for major version, minor version, patch version

So in 1.1.0, the major version is 1, minor version is 1, patch version is 0_

If you read that last point (#4), you’ll realize that this means it’s up to my package manager to decide which version to install. It could install PackageB@1.1.0, or PackageB@1.999.999, depending on which version is available, and if there any other constraints in your project

right…. so what’s the problem here?

Imagine this scenario: You branch out to create a new feature in your NodeJS app and add a certain “PackageA”@1.0.0 (which, in turns installs “PackageB”@1.1.0) and go on to build a shiny, new feature (realistically, you’d probably need way more than just 1 package to build something, but bear with this example for a sec 😅)

In a branch parallel to yours, your colleague happens to install a “PackageC” that has a dependency on “PackageB”@~1.1.16 (~1.1.16 means 1.1.16 or any patch version greater than 1.1.16, like 1.1.17, 1.1.25) - which is compatible with the “PackageA” you installed. No issues so far. You both finish your work and merge to a parent branch. Test cases pass, QA approves, app is deployed, you’re both in the home stretch! Time to work on the next few features.

But wait! Unknown to you, a month later, the latest “PackageB”@1.1.17 is released - and it introduces a bug in “PackageA”’s code, that is not easy to re-produce but is fatal to the app when it does.

Assuming a default npm or yarn setup, in the next deployment when npm install or yarn install is run, “PackageB” gets updated to 1.1.17 and the app is deployed. 2 days later a user faces the bug, and the feature that was stable for a month now crashes the app. Good luck debugging that!

And in a nutshell that is the hair-pulling issue we faced at Snowball, where a seemingly unrelated dependency caused an app crash, but only in the new iOS26, and only in a component that we wrote months ago!

.jpg)

damn you, javascript!

Maybe you too, like me, feel like shaking your first at the Node overlords, or at why the 98.9% of the web runs on this cursed language…

_Fun Fact

There’s a community-made collection of all the insane quirks and peculiarities of JavaScript in a Github Repo called WTFJS_

One way around this is to pin all your package versions and dependencies. None of that ^, ~, or minor/patch nonsense. But then, you risk losing out on important updates and security patches (the reason this system exists!)

But of course, there’s a reason we all use JS, and there is always a way around these issues! The fix that we implemented was instituting frozen lock files by default

what are frozen lock files?

The idea of a lock file - to lock down all app dependencies and conditions - should have been enough. But as I’ve just described, it can still have some issues. And that is why we have frozen lock files - lock files that cannot be edited or modified by anyone, including the package manager, even if there are package upgrades that are compatible with the app

So in our earlier example, if we froze our lock file after making our changes, “PackageB” is frozen @1.1.16, the stable version for our app. Later when we run, yarn install in a future deployment, the lock file is frozen, and so the package manager retains all lock file package versions. No bug! Problem solved 🎉

so are we in the clear? (spoilers: not really 😕)

The two safeguards mentioned above, blocking automatic lifecycle script executions and freezing your lock files, are powerful and quick improvements you can easily add to your Node JS app

But they’re not bulletproof. Malicious and buggy package updates can still occur if you decide to add a new package or need to upgrade an existing one, as you have to un-freeze your lock file to make any such changes. There’s no substitute for due diligence. Here are some pointers to always keep in mind:

- Always read release change logs for all your packages. As a developer, you need to own the changes you introduce, even if they are through an external library

- Ensure your installation commits are not coupled with feature changes. By doing so, you’re just upping the difficulty for yourself if you hit a bug and have to debug!

- (bonus) If you do have to debug, use

git bisectto find the bad commit - it helps you binary search through your suspect commit range to find the bug (thank yougit😮💨)

in conclusion

This is part of our series of documenting the engineering bridges and hurdles we cross while we build Snowball.

Be sure to check out (the now improved!) Snowball App.

And finallly, HMU if you’re working with React Native and want to join our community! You can email me here

.jpg)